Author

Reid Davis

Mentor

Melanie Palomares

Psychology 228 (Laboratory in Psychology) is a capstone class for psychology majors and minors. The main goal of the course is the completion of an independent research project, which the student develops themselves from idea to data analysis over the course of the semester. The instructional team is led by faculty member Dr. Melanie Palomares and dedicated graduate students. The 2019-2020 graduate student team consisted of Wendy Chu, Kristin Kirchner, Samantha Langley, Jaleel McNeil, Jonathan Rann, and Daria Thompson.

Students were encouraged to develop a study based on their personal interests such as social media, interpersonal relationships, or exercise. Following certification in human subjects training, the students collected data by deploying surveys and assessments to their target demographic. Students analyzed and interpreted their data using SPSS, a statistical software. Students then wrote a full length, APA style research paper about their project. Students from this class acquired several skills such as responsible research conduct, survey creation, statistical software analysis, and professional writing. This class provided the opportunity for undergraduate students to preview the graduate student research experience. The students published here went the extra mile and prepared their research papers for this publication, which often included additional, more sophisticated data analysis and new research questions.

Abstract

College students are consistently at risk for depressive behaviors during a major time of habit transition (i.e., a time of gaining autonomy while developing their own lifestyle and health habits) and gaining in independence; this is met with only half of them not engaging in at least moderately vigorous exercise (Catellier 2013; Powell, 2019). The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of types of exercise (cardio, weightlifting, and yoga/pilates) that undergraduate college students voluntarily engaged in on their subjective current and general happiness levels. There were 52 participants in the study, all undergraduates at the University of South Carolina. 88.2% were female, 9.8% were male, and 2% did not respond. The data were captured on a self-reported survey over the course of 8 weeks. Results showed no significant correlation between types of exercise linking to either current or general happiness analyses. However, findings did conclude a small positive correlation between hours exercised per day per week and current happiness levels, in that those who exercised for one hour, 2.33 days or more, per week were happier at their current state. Future research with a more well-rounded sample of sexes and ages and a more systematic measure of the variables would lead to greater understanding of the effects of exercise on college students’ mental well-being.

The Impact of Weekly Workouts on Self-Reported Happiness Among College Students

The use of exercise to promote happiness levels in individuals has been widely researched in various contexts. A systematic review of over 1150 records, studies, and interventions proved that the benefits of exercise are vast and heighten self-reported levels of happiness, even from one day of exercise per week (Hannan et al, 2018; Zhang & Chen, 2018). Even moreso, individual happiness will lead people to being more willing to actively exercise (Kiviniemi et al, 2007; Catellier, 2013). However, there is not only a shortage of information in discussing the effects of exercise on happiness, but there is also little evidence that has been concluded on which specific workouts (cardio, weightlifting, etc.) have the greatest effect on mood elevation. This research will not only address whether or not any actively-induced physical activity has an effect on a college student’s self-reported happiness, but also which exercises elevate happiness the most.

Motivational Influence on Physical Activity

Research in understanding the various motivational factors behind why people want to exercise has been built on the foundation that motivation drives us to act (Hannan et al, 2018). This motivation has been proven to be partially motivated by internal motivational processes (‘I am motivated to exercise harder because I want to be happier’) and coupled with external motivations in group settings (‘I am motivated to exercise harder because I want to impress people in this class’) (Jones et al, 2017). Motivation can lead people to exercise through intrinsic psychological forces (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000). Intrinsic motivation is an internal force leading to reasons why people exercise, such as for personal enjoyment, which could possibly lead to happiness. Psychological forces link to mood consequences associated with exercise (Vallerand, 1997). Each of these consequences can produce positive outcomes from exercising, including concentration on tasks (Jackson & Eklund, 2002; Vlachopoulos et al, 2000).

Exercise Linking to Happiness

Research has found a clear correlation between self-reported and objectively-measured physical activity and the participant’s happiness (Lathia et al, 2011; Zhang & Chen, 2018). The American College of Sports Medicine distinctly guides people for how to workout efficiently and recommends a minimum of 150 minutes of weekly exercise (US Dept. of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2018). However, these recommendations by the ACSM do not include how much the physical activity an individual partakes in affects their mood (Powell, 2019). Previous research has found that physical activity is associated with increased self-reports of happiness, along with this relationship being inversely related (Piqueras et al, 2011). Previous research has proven that a mixture of aerobic exercise and stretching showed evidence of increased happiness in multiple trials, emphasizing the impact of physical activity on mood (Zhang & Chen, 2018). Happiness links to mood in discussing life satisfaction and personal fulfillment, and has been researched in reciprocal relationships with physical activity in the current literature.

Levels of depressed attitudes among college students are increasing during this time of independent habit development (Catellier, 2013). Physical activity in college student’s lives is not a main priority, as less than half (49.9%) of college students adequately meet the 2019 American College of Sports Medicine’s suggested amount of physical activity (Powell, 2019). Therefore, the main aim of this study is to determine the effects of weekly exercise on self-reported happiness. This research studies the impact of a college student’s physical activity in correlation to their self-reported happiness during a time of habit transition at college. This study’s definition of habit transition is the time of transitioning from supervision to independence and the individual’s personal actions as a result from the transition.

Healthy Lifestyles

Previous research has shown how a minimum of 30-minute workouts once a week could improve mood in pilot studies (Powell, 2019). Physical activity included weight lifting, yoga/pilates, High Intensity Interval Training, and walking/running. Each 30-minute session was once a week, for 2.5 hours total, over 5 weeks. The pilot’s findings concluded that participants experienced heightened positive emotions after physical activity. This study addresses the relationship between physical activity and mood on a smaller sample size.

Happier People Living Healthier Lives

Many studies have been conducted to either evaluate people’s individual happiness levels or how exercise affects a certain behavior. Few studies have used self-reported surveys to capture participant’s happiness levels and their differing exercise habits. Piqueras et al. studied the happiness and health behaviors in Chilean college students, in which they distributed a survey to 3461 students between 17-24 years old (M=19.89, SD=1.73) (Piqueras et al, 2011). The study measured the healthy behaviors of the college students using an objective index, including smoking, stress levels, nutrition intake, and frequency of exercise. The findings of the study conclude that the relationship between happiness and healthy behaviors are linked, in that stress and happiness were correlated in an inverse relationship. The increases in frequency of exercise were positively correlated to higher levels of happiness.

Lathia et al. studied how varying degrees of physical activity, including non-exercise, is linked to increasing happiness (Lathia et al. 2017). The researchers used a smartphone application (Google Play Store app; captured using an accelerometer) to measure the relationship between any degree of self-reported physical activity (PA) (independent variable) and self-reported happiness (dependent variable).The app measured behavioral PA through the accelerometer feature on the participant’s phone. Participants were members of the general public, from 25-34 years old. The study used over 10,000 useful participants (n=10,889), 43% being female and 54% male (3% did not disclose). Results concluded that those who are more physically active, even in non-typical exercise formats and settings, self-reported as happier. These findings are sound on the basis of subjective self-reports and through objective app-based reports (Lathia et al, 2011).

Knowing that degrees of physical activity can lead to individual’s self-perceived happiness levels, focus is turned to the behavioral outcomes of an exercise class. This study used 417 female participants to track the behavioral outcomes (among others) following a structured exercise class. This study enhances my project because it highlights research that focuses on how behavior (dependent variable) is linked to exercise when the exercise type is manipulated (independent variable). Findings conclude that those who have higher attentional styles (i.e., better abilities and ways to stay engaged throughout the class) reported significantly better behavioral and positive outcomes and the participants were greatly more self-determined (Jones et al. 2015). This shows that attentional styles are most likely linked to both long-term motivation and positive behaviors.

Previous literature links physical activity (PA) and happiness. The authors used 15 observational and 8 interventional studies to evaluate, and there were neither age nor condition limits for the participants. However, studies considered to be included had to meet a certain criteria through assessment for each individual’s perceived happiness level. Findings conclude that among the 13 cross-sectional observational studies, the link between PA and happiness were universally significant among a wide range within the sample studied. The findings also suggest that both PA frequency and volume within a certain time frame are very significant in the correlation between PA and happiness. While there was no significant difference found across varying cultures, as little as 10 minutes of PA per week could increase happiness (Zhang & Chen, 2018).

For this study, the hypotheses is that college students at the University of South Carolina who participate in any type of workouts will self-report as happier either on the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), ranging from not a very happy person to a very happy person, or on the Likert Scale; and college students at the University of South Carolina who participate in any amount of exercise will self-report as currently happier on the Likert Scale . If the self-reported happiness levels are linked to the type of workout, then the SHS and Likert Scales will be higher ranked. If the self-reported happiness levels are linked to the number of workouts per week, then the Likert Scale will be correlated to the presence of workouts per week. As the type of workouts in the week stabilizes (are more the same), then self-reported happiness will be higher, either from the Likert scale or SHS measures. As the number of workouts in the week increases (including if people participate in workouts at all), then current self-reported happiness will be higher, from the Likert scale.

Method

Participants

The data analyzed for this study were taken from the distributed, 18-question, multiple-choice survey (Appendix B). Following CITI Human Subjects approval (the policies and procedures needed for undergraduate researchers to gain approval to investigate), the survey was dispersed to undergraduate students at the University of South Carolina. (CITI differs from IRB (Institutional Review Board), which ensures that a certain study is ethical to run. It was not needed for this research.) The participants were registered in various colleges and schools in the University. The majority were in the College of Arts & Sciences, with Bachelors of Arts or Sciences in Experimental Psychology (36 participants; 73.3% of the responses for this question). A total of 52 undergraduates participated. 51 participants were included in the sample; 1 participant’s datum was excluded for not answering all of the questions. Participants were recruited through five class Listservs, with no incentives provided. 88.2% of the participants were female; 9.8% were male; and 2% did not respond. Ages for the participants ranged from 18 to 22 years old, with two 26 year olds as outliers. No freshmen participated in the survey; 27.5% were sophomores; 29.4% were juniors; and 43.1% were seniors and/or undergraduates taking more than four years to complete their degree.

Materials

Google Form Questionnaire

Participant’s demographics and weekly exercise reports were measured in a Google Form Questionnaire that was distributed to the undergraduates. Participants were asked to respond to the multiple-choice formats to measure hourly exercise rates per week, workout type engagement, and number of workouts per week. Participants needed either a Gmail or University of South Carolina-Columbia email to answer the form, along with access to a computer or smart device and internet connection. This questionnaire was anonymous and included a required consent approval prior to starting. The development of the survey included demographics, weekly workout routines, and levels of happiness (explained below).

Subjective Happiness Scale

Participant’s individual general happiness was measured through the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1997). The original Subjective Happiness Scale is a four-question census that ranges on a 7-point Likert scale, anchored from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a great deal). However, for this study, participants were asked the same four questions from the original SHS with the same anchors (not at all to a great deal) but with a 3-point multiple-choice format. Each question derived from the SHS had three multiple-choice options: not a very happy person, an occasionally happy person, or a very happy person; and not at all, sometimes, or a great deal, when asking about how a specific scenario applies to them. The SHS has been used in a collection of research studies for positive psychology interventions and interpreting motivations and emotions (Seligman et al, 2005; Lyubomirsky & Tucker, 1998).

Likert Scale

Participant’s current happiness ratings were measured through a ten-point Likert scale, anchored from 1 (not happy at all) to 10 (extremely happy). This question was embedded in the demographics section.

Procedures

The survey was created entirely on Google Form. Each participant completed the Google Form survey, with the accommodated Subjective Happiness Scale included into the 18-question census. The surveys were distributed through five undergraduate psychology courses at the University of South Carolina and could be completed at any time of the day or week. The survey was distributed through class email Listserv’s through class Blackboard sites and study group GroupMe’s, a group-based text messaging software. The entire questionnaire took approximately five to six minutes to complete and submit.

Design and Analysis

Subjective Happiness Scale on the Google Form

Participants answered all of the questions through either a Likert scale or a multiple-choice format. The three-question multiple-choice answers were analyzed and accommodated for the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) by associating the earlier letters of the alphabet given negative numbers; the middle letter was neutral (so given zero in the computation); and the later letters of the alphabet given positive numbers. The three-question multiple-choice psychometrics were from A to C (A = -1, B = 0, and C = +1) and plugged into SPSS. A = not a very happy person, B = an occasionally happy person, or C = a very happy person; and A = not at all, B = sometimes, or C = a great deal were the anchors. This was utilized to measure participant’s general happiness ratings.

In addition to the SHS, each participant stated in the survey the type of workout they do the most often into nominal categories. The three types of exercises were cardio, weightlifting, or yoga/pilates. The majority of the participants (65.3%) selected cardio. These groups were decided in advance and applied in the multiple-choice format for participants to select. Each participant also stated the number of workouts they completed per week. The operation definition of a workout was the ‘attempt(s) to accelerate heart rate for a minimum of 20 minutes per session (i.e., the active pursuit of “going to workout”)’. Workouts excluded physical labor jobs, walks to class, and/or any other qualifying excursion not taken in the goal of completing a ‘workout’. The majority of the participants (52.9%) completed 0 to 2 workouts per week.

Likert Scale

The Likert Scale was to measure participant’s self-reported happiness levels at their current state, while taking the survey. The single-question Likert scale prompted the student to rate their current feeling of happiness from 1 to 10.

A between-subjects ANOVA was utilized to analyze the Likert-scale-measured happiness levels among three different types of exercises. The independent variable was the exercise type, and the dependent variable was the current happiness level of each participant from the Likert scale. Another between-subjects ANOVA was utilized to analyze the Subject Happiness Scale measurement among three different types of exercises. The independent variable was the exercise type, and the dependent variable was the general happiness level of each participant, ranging from “Not a very happy person” to “A very happy person”. Two ANOVAs were conducted to confirm the findings using two methods of ‘happiness’ capture and to resolve if different types of exercise affects happiness levels currently or generally-speaking, from a subjective perspective. A Pearson Correlation was also utilized to analyze the link between if people exercise or not and their correlating current happiness levels. The independent variable is exercise amount, if any, during the week of each individual. The dependent variable is the current happiness level of each participant (taken from the Likert scale). Using the results from the Google Form, all data analyses were conducted using SPSS.

Results

The study hypothesized that college students at the University of South Carolina who participate in any type of exercise will self-report as happier either on the Subjective Happiness Scale or on the Likert Scale, both measured to capture current and general happiness ratings. It was also hypothesized that those who participated in any workouts at all during the week will self-report as currently happier on the Likert scale. To test these hypotheses, three analyses were simulated: two between-subjects ANOVAs and one Pearson Correlation. Between-subjects ANOVA A measured the effects of different types of exercise (cardio, weightlifting, and yoga/pilates) on people’s current happiness levels using the 10-point Likert scale measurement. Between-subjects ANOVA B measured the effects of the different types of exercise on people’s general happiness levels using the 3-point Subjective Happiness Scale. The Pearson Correlation measured the link between workouts per week and happiness levels using the 10-point Likert scale measurement. For both ANOVAs, the independent variables were both ‘exercise type’. However, for ANOVA A the dependent variable was general happiness levels, while ANOVA B’s was current happiness levels. The independent variable for the Pearson Correlation was participation in exercise per week and the dependent variable was current happiness levels, measured by the Likert scale.

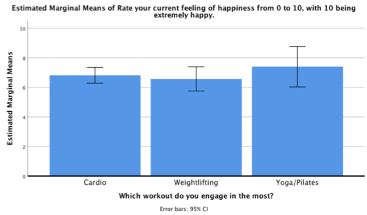

The between-subjects ANOVA A analysis was conducted on the type of exercise each individual participated in per week (cardio, weightlifting, and yoga/pilates) and current happiness levels. There was not a significant effect, F(2,49) = .548, p > .05. There was not a significant difference between the effects of either cardio (M=6.82, SD=1.424), weightlifting (M=6.57, SD=1.869), or yoga/pilates (M=7.40, SD=.894) on current happiness levels, measured by the 10-point Likert scale. The bar graph (Figure 1) shows that all of the bars and standard error measures distinctly overlap, coinciding with a not significant finding.

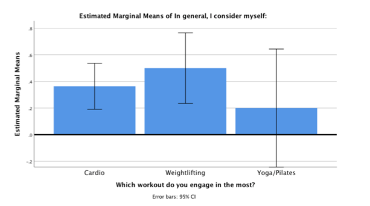

The between-subjects ANOVA B analysis was conducted on the type of exercise each individual participated in per week and general happiness levels. There was not a significant effect, F(2, 49) = .762, p > .05. There was not not find a significant difference between the effects of either cardio (M=.36, SD=.489), weightlifting (M=.50, SD=.519), or yoga/pilates (M=.20, SD=.447) on general happiness levels, measured by the Subjective Happiness Scale. The bar graph (Figure 2) shows that all of the bars and standard error measures distinctly overlap, coinciding with a not significant finding. The yoga/pilates standard error measures dive into negative numerical values, representing high uncertainty in the effects of this particular exercise on participant’s general happiness.

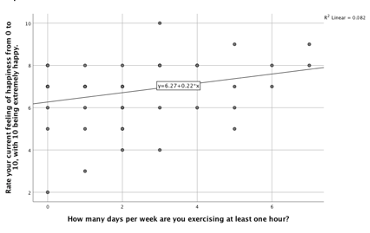

The Pearson Correlation analysis was administered on the individual’s participation in at least one hour of exercise per days per week (M= 2.33, SD= 1.966) and current happiness levels (M= 6.78, SD= 1.514). Results show a significant correlation, r(51)= .287, p < .05. The scatter plot shows a moderately positive and strong correlation between one hour of exercise per days per week and current happiness levels (Figure 3).

Discussion

This study researched the influence of different exercises on varying states of happiness. Findings conclude that the differing types of workouts (cardio, weightlifting, and yoga/pilates) did not have a significant effect either on participant’s current happiness levels at the time of taking the survey or on their subjective general happiness levels overall. However, the study did conclude that those who participate in a least one hour of exercise 2.33 or more days per week did have significantly higher levels of current happiness at the time of taking the survey. The findings do support the second alternative hypothesis, in that those who participate in any time-length of exercise during the week will self-report as currently happier.

Being that the correlation findings do positively correspond, this study does further the discussion for how exercise positively impacts adult’s mental health, since everyone was 18 years old. Nonetheless, this study’s findings are more consistent with the current literature focused on exercise-induced happiness. Since this study not only accounted for the different types of exercise but also the varying stages of happiness, it allows for advancements on the topic of how exercise of varying participation levels could account for varying degrees of mood or mental health influence across the board. This is particularly prevalent in college students, due to the increase in college depressive moods elevating in recent years (Catellier, 2013).

Based on the findings of this study, a minimum required amount of exercise daily does support the previous research surrounding this topic. It was concluded that as little as 10 minutes of physical activity per week results in mood elevation (Zhang & Chen, 2018). Piquerias et al. came to the same positive association not only between PA and happiness, but also that happier participants were more likely to exercise (2011). Future research could investigate inverse relationships such as this one mentioned. Also, because this mood elevation is not directly linked to the types of exercises performed, each type of exercise could provide a form of ‘coping’ or de-stressing strategy for each participant during stressful times on campus(Powell, 2019). Due to other events occurring in similar observational settings, it is sound to conclude that measuring the dependent mood degrees (participant’s general anxiety versus their current anxiety) would better further research in this field.

The findings enhance beliefs in the industry that exercise affects happiness at the individual’s current state and directs future individuals to participate in exercise to enhance any possible happiness or mood levels. A question in my study supports this direction, in that 84.3% of the participants in my survey would at least consider (41.2%) or definitely agree to (43.1%) working out more if they knew that exercising would make them happier. Previous research supports this finding as well, with college increasing student’s stress levels and psychological disorder symptoms (Catellier, 2013). Along with my research, other studies have anticipated how happiness could be impacted by outside influences, such as social gatherings (Lathia et al, 2011). This limitation is shown in this study too, in which future research could address the limitation through experimental controls and measures, as evidenced in Powell’s controlled experiment.

Further limitations in this study give opportunities for advancements in the field. Objective measurements of happiness (i.e., accelerometers) would be plausible versus a subjective measure. Intensity of workouts could be evaluated using objective measures as well. Since each person exercises at different degrees of intensity, even with the same exercise, it would be interesting to account for individual heart rates in relation to mood changes. A question that should also be addressed is does an individual’s motivational level over prolonged periods of time affect their mood elevation? Thus, further studies could dissect how and why people who exercise over at least one year of time are possibly less motivated and/or do not reap the same mood elevation benefits as their amateur counterparts. Also, the majority of the participants (88.2%) were female. In the future, a more balanced sample might produce different results.

As college students continue to adjust to facing mood adjustments, further research addressing how coping mechanisms like exercise could help them be happier is necessary. This is difficult, as COVID-19 has hurt opportunities for students on many campuses to attend gyms and obtain workout equipment due to shortages and shutdowns. The current pandemic will certainly present a number of opportunities to study the relationship between exercise and mood. Understanding how mood changes allows researchers to draw interpretations from their own studies in determining how exercise affects young adults during times of habit transition. However, while mood might be affected by daily exercise or lack thereof, variables associated with exercise could greatly alter mood as well.

About the Author

Reid Davis

Reid Davis

Reid Davis graduated from the University of South Carolina in May of 2020. From Charlotte, NC, Reid pursued a Bachelor of Arts in Experimental Psychology with a minor in Sport & Entertainment Management and graduated Magna Cum Laude. During her time at Carolina, she earned the Magellan Scholar for her research with the department of Health, Promotion, Education, and Behavior with Dr. Courtney Monroe and Graduated with Leadership Distinction in Community Service. Reid is currently taking a gap year to finalize her research endeavors and apply to graduate schools for her Masters in Counseling. She is also seeking a certification in personal training, and found this project to be of particular interest when combined with her passion in sports psychology. Reid hopes to obtain her PhD. and has found that this project has advanced her understanding from her previous classes and scholarly experiences to one day achieve that goal. Most importantly, Reid is very grateful to her mentor, Dr. Melanie Palomares, and teacher’s assistant, Jaleel McNeil, for their guidance, patience, and attentiveness throughout this publication, along with the Office of Undergraduate Research and Center for Integrative and Experiential Learning.

Bibliography

Catellier, J. R. A., & Yang, Z. J. (2013). The role of affect in the decision to exercise: Does being happy lead to a more active lifestyle? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(2), 275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.11.006

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Conceptualizations of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior, 11–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7_2

Hannan, T. E., Moffitt, R. L., Neumann, D. L., & Kemps, E. (2019). Implicit approach–avoidance associations predict leisure-time exercise independently of explicit exercise motivation. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 210–222. doi: 10.1037/spy0000145

Jackson, S. A., & Eklund, R. C. (2002). Assessing Flow in Physical Activity: The Flow State Scale–2 and Dispositional Flow Scale–2. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 24(2), 133–150. doi: 10.1123/jsep.24.2.133

Jones, L., Karageorghis, C. I., Lane, A. M., & Bishop, D. T. (2015). The influence of motivation and attentional style on affective, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes of an exercise class. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(1), 124–135. doi: 10.1111/sms.12577

Kiviniemi, M. T., Voss-Humke, A. M., & Seifert, A. L. (2007). How do i feel about the behavior? The interplay of affective associations with behaviors and cognitive beliefs as influences on physical activity behavior. Health Psychology, 26(2), 152–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.152

Lathia, N., Sandstrom, G. M., Mascolo, C., & Rentfrow, P. J. (2017). Happier People Live More Active Lives: Using Smartphones to Link Happiness and Physical Activity. Plos One, 12(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160589

Lyubomirsky S., & Lepper, H.S. (1999). Subjective Happiness Scale, A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155. doi: 10.13072/midss.121

Lyubomirsky, S. & Tucker, K. L. (1998). Implications of Individual Differences in Subjective Happiness for Perceiving, Interpreting, and Thinking About Life Events. Motivation and Emotion, 22, 155-186.

Piqueras, J. A., Kuhne, W., Vera-Villarroel, P., Straten, A. V., & Cuijpers, P. (2011). Happiness and health behaviours in Chilean college students: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health, 11(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-443. Retrieved from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-11-443

Powell, L. D. (2019). The effects of a physical activity program on mood states in college students., 67. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/dd7cbfeb45ed3e07b9e43bcf9f8813f5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Volume 29, 271–360. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60019-2

Vlachopoulos, S. P., Karageorghis, C. I., & Terry, P. C. (2000). Motivation Profiles in Sport: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(4), 387–397. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2000.10608921

Zhang, Z., & Chen, W. (2018). A Systematic Review of the Relationship Between Physical Activity and Happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1305–1322. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9976-0

Appendices

Appendix A. Figures

Figure 1 - Between-subjects ANOVA A

Figure 2 - Between-subjects ANOVA B

Figure 3 - Pearson Correlation

______________________________________________________________________________

Appendix B. Survey Questions

- By clicking this box, I agree to participate in this study for a student project for PSYC 228. I volunteer to give information, and I can refuse to answer any questions. I am aware I can stop at any time. Contact Information: Researcher: Reid Davis (ellad@email.sc.edu) 704.995.0891 Facility Supervisor: Melanie Palomares (paloma@sc.edu) 803.777.5453 *required

- Yes I consent

---Demographics------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- What is your biological sex?

- Male

- Female

- Prefer not to say

- Age? ____________

- What year are you in school?

- Freshman

- Sophomore

- Junior

- Senior

- What is your major? ____________

- What is your race?

- Asian

- Black

- Hispanic/Latino

- Native American/Pacific Islander

- White

- Prefer not to say

- Rate your current feeling of happiness from 0 to 10, with 10 being extremely happy.

- 1...10 (Likert Scale)

- How many days per week are you exercising at least one hour? ____________

---Questions------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- On average, how many hours per week do you exercise?

- 0-2 hours

- 3-5 hours

- 6-8 hours

- 9+ hours

- How motivated are you to work out beforehand?

- Not at all, ever

- Sometimes, depending on the day or workout

- Almost everyday

- Which workout do you engage in the most?

- Cardio

- Weightlifting

- Yoga/Pilates

- How many workouts do you partake in per week? (Workouts for our survey are defined as active attempts to accelerate heart rate for a minimum of 20 minutes per session (i.e., the active pursuit of “going to workout”), so this excludes walking to class or a physical-labor job).

- 0-2 workouts

- 3-4

- 5-6

- 7-8

- 9+

- Do you have a workout buddy?

- Yes

- No

- Sometimes, depending on the day or workout

- In general, I consider myself:

- Not a very happy person

- An occasionally happy person

- A very happy person

- Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself:

- Not a very happy person

- An occasionally happy person

- A very happy person

- Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you?

- Not at all

- Sometimes

- A great deal

- Some people are generally not very happy. Although they are not depressed, they never seem as happy as they might be. To what extent does this characterization describe you?

- Not at all

- Sometimes

- A great deal

- Would you exercise more times per week if you knew it would make you happier?

- Yes

- No

- Maybe, depending on the day or workout